March 8, 2019 — I happened across Ingrid Hempell in the Clayton Post Office, earlier this week. I haven’t seen Ingrid since we wrote her life story in a three-part series in the Diablo Gazette in October-December of 2017. Her story is one that should be told, and one that I won’t forget. However, there is a real fear that invaluable lessons are becoming lost on the future generation. Ingrid is passionate when she insists that the WWII atrocities must continue to be documented and told. It’s time that we re-tell her story.

(Diablo Gazette, October 2017) Clayton’s Ingrid Hempell: Life in Postwar in East Germany

[Ingrid Hempell is now retired living in Clayton. Many may remember her French restaurant, La Croquet, which is now Moresi’s Chop House. After attending the life story presentation of Auschwitz survivor Bernie Rosner at Rotary of Concord Rotary and Concord-Diablo Rotary luncheon on September 8, Hempell stood up to convey her concerns. The horrific history of WWII and its consequences, the human toll is getting lost on today’s children. She fears that apathy will cause invaluable lessons to be forgotten in future generations.

Hempell is now offering her own life experiences in speeches that reveal the dark side of what the history books do not communicate. She lived in Berlin, Germany, and was three years old during the allied bombing of Berlin and the eventual surrender of Germany. In this three-part series, Hempell describes the painful years of growing up under communist rule behind the wall and her eventual journey to America, a country which she is eternally grateful.]

Bombed, Occupied, and Isolated

The end of Hitler’s “One thousand Year Reich” in May of 1945 followed one of the most diabolic human atrocities in history, because it included the willful murder of innocent men, women, and children, and the development of a brutal blitzkrieg war machine.

“My childhood and youth were spent in a desperate world of rubble and ruins, of hunger and cold, and the loss of my father,” Ingrid begins.

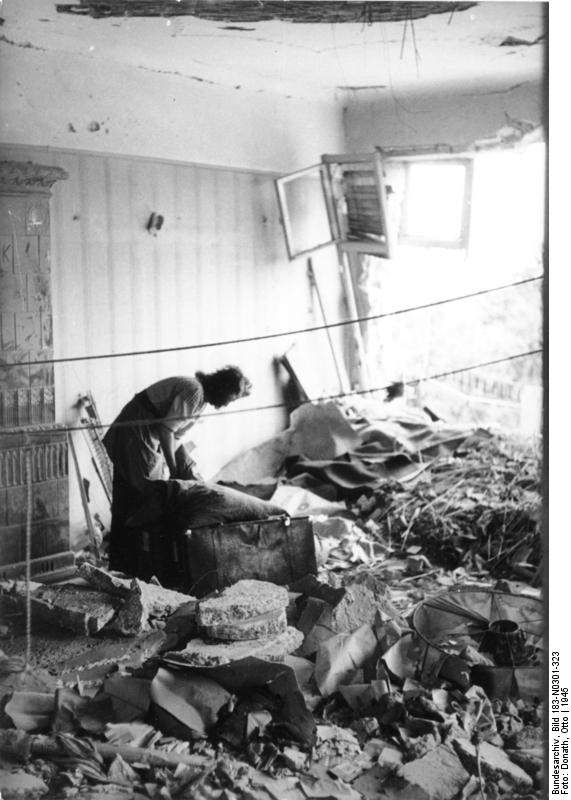

“Being born in 1941, I do not remember too much about the war itself. But etched in my memory are the terrible sounds of the sirens announcing the approaching planes carrying the bombs that would fall on Berlin. At night, my mom would pull me out of bed, wrap me in a blanket and race with me to the bomb shelter in the cellar of the four-story house where we stayed with my grandparents, next to the historical Zion’s Church (built in 1873). I was too young to fully understand what was going on, but the fear in the eyes of the grown-ups affected me. Then came the sounds of the explosions, closer and closer, until the walls rattled, some plaster fell, and the lights went out. My mom tried to comfort me as I cried. After the explosions stopped, there was an eerie silence, and then the lights came back on. The grown-ups started talking in hushed voices, and some would smile a little in relief. The last bombing attack on Berlin happened April 21, 1945.

“The building we were in was spared, but the rest of the street and the apartment house where my parents used to live was completely demolished. Later, my mom found my burnt baby carriage in the rubble.

“We lived in the part of Berlin that later became East Berlin. My father, a furniture maker, was forced to join the war effort. He could come home for a short period in December of 1944 because his father was ill, but by the end of the month, he had to leave, otherwise he would have been declared a deserter, punishable by death. We never saw or heard from my father again. We received no news of his whereabouts either. He was just missing. For the rest of her life, my grandmother kept repeating, ‘Mine Ernst, oh, mine Ernst, where is he? He must come home to me again.’ My father’s brother lost one leg in the war, but at least he came back.

“When the war ended on May 9, 1945, Berlin was a wasteland, as was most German cities. The winter of 1945-46 was extremely harsh. We were cold and hungry. Many, more people died, especially the elderly. The allies had divided Germany and Berlin into four occupation zones, the American, the British, the French, and the Russian sectors. Berlin was located like an island in the middle of the Russian occupied zone.

“When the Russians arrived in Berlin in 1945, they took a terrible revenge on the German people. It is still called the ‘Rape of Berlin’. There were about 130,000 victims. All civic ways and means of getting supplies to the people had collapsed, and there was no hope of things getting better anytime soon.

“The Russians established a Communist political and economic system in East Germany. Banks, farms, industries were seized and re-organized. Natural resources, leftover equipment, even our scientists were taken to Russia. Protesters went to prison. Laws, currency, and school systems changed under the new Communist leader Walter Ulbricht. In school, it seemed that the main subjects were all about the Great Russian October Revolution of 1917 and their various five and ten-year achievement plans. Russian language studies became mandatory. The state controlled the press, churches, and education. Western news, radio, or papers were not allowed. Trade and travel were restricted. The Iron Curtain cut off Eastern European satellite states, East Germany and of course East Berlin from the rest of the world.”

(Diablo Gazette, November 2017) Life in Post-War East Germany

In 1945, after Germany had fallen, Berlin was a wasteland, and Germany and Berlin had been divided into four occupation zones, Ingrid lived in the zone awarded to Russia. The children were encouraged to join communist youth groups.

“I came home from 5th grade one day and asked my mother if I could become a young pioneer so I could wear that blue neck scarf. She had a fit,” Ingrid recalls. Russian children wore a red scarf and only a few people in her school had that privilege. It reminded Ingrid of the Hitler youth programs. Under communism, higher education was only possible with very strong political consent to the establishment.

They were impoverished. Ingrid’s Mom worked as a Truemmer Frau. She and thousands of others worked in the fields of rubble, removing debris, and cleaning and stacking bricks for re-use, all by hand. When she came home, her gloves were worn out and hands were half frozen.

Occasionally, Ingrid’s mom would ride the train to the outskirts of Berlin with a small backpack of her father’s tools. After two or three days, she would return from bartering with farmers, perhaps bringing a few eggs, slice of bacon, bread, or some potatoes.

“When we were lucky enough to have a few potatoes, I wanted to help my grandma peel them, but she always refused. Perhaps she worried that I would cut too much off. Sometimes, she would not let me touch them because some were half rotten and smelly. At one point, my grandfather left home with his greatest possession, a square radio called a Volksempfaenger. Hours later, he returned from the black market with two loaves of bread.”

Tensions increased between the WWII allies and historians see this as the start of the Cold War. In time, the Russians became upset about the way West Berlin was governed and prospered. So, in June 1948, they blocked all access to West Berlin hoping they could then take over.

But the allies organized a gigantic airlift to supply two million people in West Berlin with food, coal, medication, and everything else.

That year the American Marshall Plan gave $13 Billion dollars ($132 Billion in today’s currency) to jump start the economies in Germany, England, and France. The Soviet Union refused to accept the help. After eleven months, the Russians gave up and ended the blockade. Several pilots had paid with their life to support the people in West Berlin.

“On the few occasions that my mother took me to the West, we marveled at all the things that were available in their stores: oranges, bananas, chocolates, clothing, shoes, pastries, even toilet paper. We had none of that,” Ingrid stated. The food stamps were not enough, water and electricity outages were frequent. Neighbor would alert neighbor if a produce store just received fresh produce.

“Sometimes, we were told that strawberries had arrived. We would rush down to the store and stand in line for an hour only to be told they were sold out by the time we got to the front of the line.

“My mother worked on street cars collecting fares, and I was mortally afraid that she might not come home during those days,” Ingrid recalls. The rebellion was crushed in a couple of days.

“In 1949, I was eight years old. I had already spent a lot of time with various care homes: a catholic convent where nuns spanked us frequently, sometimes with my grandparents which were the best of times, or with my mother. We moved countless times with a hand drawn wagon since we didn’t have a home. The war had torn the country and millions of families apart.

Food was rationed, and it was never enough. There were shortages of everything. Communist oppression increased until in 1953 strikes and riots broke out. Overnight, Russian tanks and troops were everywhere and there were shootings in the streets.

One dark secret of the DDR was the politically motivated parental child abduction. Parents were expected to teach their children to become faithful to the communist doctrine. There were thousands of different scenarios where children were taken from uncompliant parents, sometimes right after birth, and then given to communist adoptive parents. The grief and sorrow of the victims are still felt today. People are still searching for their lost children.

Due to all the hardships, thousands of East Germans fled to the West every week, approximately 3.5 million people. After 1953 all borders between East and West Germany were closed and secured by barbed wire fences, watch towers, and armed militia. The only window remaining open was in Berlin because it was still under authority of the four Allies.

In 1957, Ingrid worked at the Weissensee Children’s Hospital hoping to one day become a nurse. In the first year, she witnessed a baby dying. It affected her deeply and reminded her of stories she heard from her mother’s friend who had survived in a concentration camp. Ingrid would overhear stories of how the guards would brutally kill children. Such conversations were difficult to keep private when everyone lived in just one room.

(Diablo Gazette, December 2017) West Berlin Refugee to Clayton Restauranteur

In 1960, Ingrid’s mother defected with her two half-brothers to West Germany and found a refugee shelter. She had stayed behind to in the apartment and continued her schooling and hospital work.

Then the US summit with Nikita Khrushchev in Paris collapsed in May of 1960, after the Russian shot down an American spy plane. Russia enacted Martial Law in East Berlin and placed troops everywhere. For fear that the Russians may close the Berlin border permanently, her mother plead for Ingrid to defect. Ingrid resisted. “I liked my independence, my apartment, my work, my friends. I was naïve. I thought the Americans would never allow me to do that.” Fortunately, her mother convinced her to leave.

Leaving East Berlin was considered a crime deserving of jail or even death. In one infamous case, a young man named Peter Fechter attempted to climb over the Berlin wall. Border guards shot him without warning. He fell back to the Eastern side, agonizing in pain, crying for help, but no one would. He bled to death. In all, approximately 240 people died trying to cross the wall to reach freedom.

Before the wall was built, you could cross the border by foot, train, or subway. But border guards were fierce. You had to leave all your belongings behind.

Ingrid planned her escape but on May 1960, her attempt was thwarted. Her neighbor’s brother was a young East German soldier. He had discovered her plans and felt it was his duty to the Vaterland to stop her. He pulled his gun to take her to the police station. This meant she would never see her family again. She begged, cried and fabricated a story of having a fiancé in West Berlin. She convinced him that he would be ruining her life. Fortunately, the very young soldier let her go. And at 17, Ingrid found her mother in a West Berlin refugee camp and was free at the age of 17.

From then, Ingrid finished nursing school in Bavaria in May 1963 and in June 1965 she immigrated to America to New York with no friends, no money, and could not speak English (speaking Russian was no help).

“I don’t know if I was too courageous or just ignorant, or both. But I was 23 years old and wanted a new life. And this country was very, very good to me. God Bless America!”

In time, Ingrid met and married Rudy Hempell. Together they operated restaurants, and eventually moved to Clayton where she and her husband owned and operated La Cocotte, a lovely French restaurant until she retired. Rudy passed away November 22, 2018. Thank you for sharing your story in such detail. Live long Ingrid, Clayton adores you.