By Ricard Eber

As news of violence against Asians in the Bay Area occupies the headlines today, March quietly marked the 75th anniversary of the final closure of the Japanese internment camps and release of prisoners.

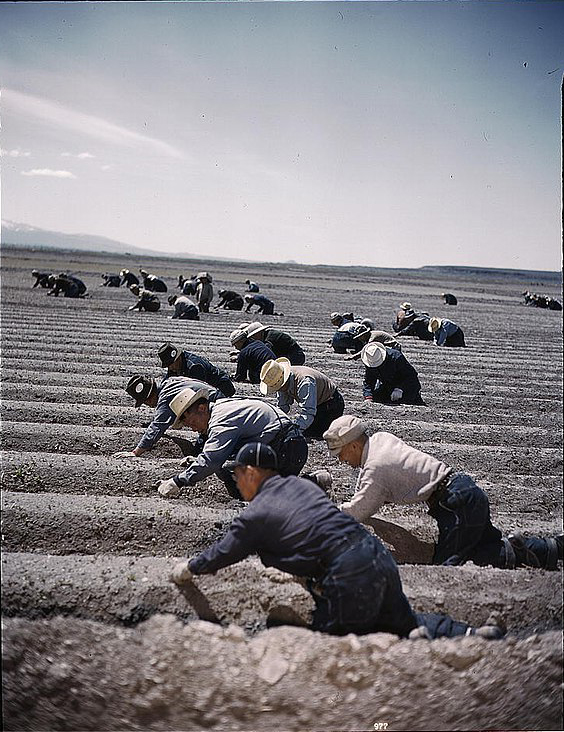

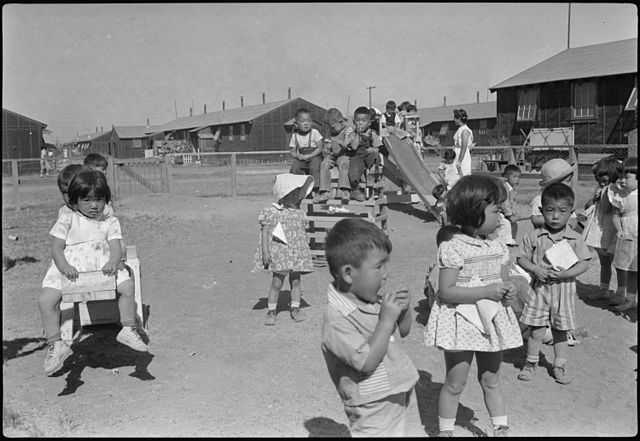

In 1942 approximately 120,000 Japanese, over two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens, were forced to leave their homes and move into one of 10 camps that were established along the West Coast by the War Relocation Authority (WRA). The most controversial camp that housed the largest number of internees was Tule Lake. The last camp to release its prisoners, it did not close until March 20, 1946, seven months after the end of World War II.

At the end of World War II, Japanese Americans faced rebuilding their lives. The Issei (first generation) had lost almost everything and forced to completely restart. In the 1960’s, Sansei (third generation) joined other people of color in the Civil Rights movement and the quest to learn of their suppressed histories through ethnic studies. Many Sansei learned their families had spent WWII in American concentration camps.

As awareness of the wrongfulness of the incarceration grew, Japanese American community activism succeeded in getting the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (CLA) passed, and survivors received an official apology, token $20,000 payments, and a promise to fund education about the incarceration to deter future violations.

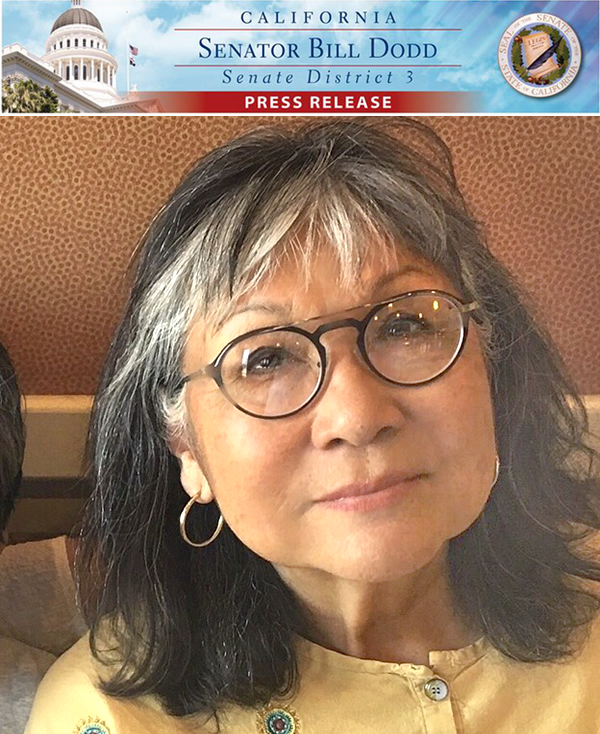

So, shouldn’t Jean Yokotobi be angry? Her mother and father found themselves incarcerated for national security reasons, rounded up by Federal Agents following Pearl Harbor in 1942 by order of President Franklin Roosevelt. They spent almost four years at Tule Lake. Yokotobi was born in Camp Tule Lake in 1945. She now lives in a small delta community of Isleton. A town whose Asian-American history is so rich, it has been designated a National Historical site.

Isleton is a city in Sacramento County with a population of about 840. Surprisingly, Yokotobi harbors no ill will. Growing up in the Central Valley town of Gridley, Yokotobi’s parents never discussed their imprisonment with her, nor did they blame Roosevelt for his actions.

“Mom and dad were loyal patriotic Americans who spoke proudly about the highly decorated Japanese military battalions that fought bravely in Europe that helped liberate the extermination camp at Dachau from the Nazis. They never complained about the Alien Land Law of 1913 or other forms of discrimination Asians faced,” she says.

Instead, she recalls learning toleration attending Buddhist Sunday School as a child. “My parents taught us honor and respect for others.”

Yokotobi was not even aware of her parents’ internment at Camp Tule Lake until she attended college at San Francisco State in the mid 1960’s.

While at SFS, she visited a boyfriend in the tiny Sacramento River Delta town of Isleton and fell in love with it. She eventually settled there, opened a deli and restarted the Isleton Chamber of Commerce, becoming its president. She is also a past president of the Isleton Historical Society and is working on building a museum celebrating the Japanese and Chinese heritage that has resulted in Isleton being designated to be a National Historic Landmark.

As head of the Chamber and a leading citizen of Isleton, Yokotobi’s has dedicated her heart and soul and devoted her retirement to promoting her adopted community of Isleton and preserving its Chinese- and Japanese-American heritage. Even Sen. Bill Dodd named her Sacramento County Woman of the Year.

Sitting in the historic Isleton building she owns, replete with pictures and artifacts from the town’s colorful past, Yokotobi is eager to pass on this rich Asian heritage to others.

Next door to her is the restored structure which was once the headquarters to the Tong. Chinese immigrants, having few civil rights, congregated in this gathering place to settle disputes, socialize, and preserve their Eastern heritage. This summer a new museum is expected to open.

Just down the street is Iva Walton’s Mei Wah Beer Room. It too is a relic of Isleton’s past that includes a replica of an Opium Den. This is a great place to drink a local draft beer after scoring homemade sandwiches from the nearby McBoodery Café.

My passion for Isleton will always remain,” Yokotobi said. “It has given me a sense of worth, a sense of peace, and a sense of hope for the future. I sincerely hope when the Asian-American Heritage Park is completed, people can reflect and feel good about what they are taking away from their experience in Isleton.”